As I was selecting a Thanksgiving Menu this year I was struck by the thought that much of the menu may not have even been at the first Thanksgiving which prompted me to do some research.

According to HISTORY.COM much of what we eat today for Thanksgiving is vastly different from the First Thanksgiving.

As I was selecting a Thanksgiving Menu this year I was struck be the thought that much of the menu may not have even been at the first Thanksgiving which prompted me to do some research.

Today for many Americans, their traditional Thanksgiving meal includes many “seasonal” dishes such as roast turkey with stuffing, cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green bean casserole and pumpkin pie.

As an annual celebration of the harvest and its bounty, moreover, Thanksgiving falls under a category of festivals that truly spans cultures, continents and millennia. Thanksgiving itself dates back to November 1621. For more than two centuries, days of thanksgiving were celebrated by individual colonies and states. But, it wasn’t until 1863, during the midst of the Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed a national Thanksgiving Day to be held each November.

Although the American concept of Thanksgiving developed in the colonies of New England, its roots can be traced back to the other side of the Atlantic. Both the Separatists who came over on the Mayflower and the Puritans who arrived soon after brought with them a tradition of providential holidays—days of fasting during difficult or pivotal moments and days of feasting and celebration to thank God in times of plenty. Historians have noted that Native Americans had a rich tradition of commemorating the fall harvest with feasting and merrymaking long before Europeans set foot on their shores. In ancient times, the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans feasted and paid tribute to their gods after the fall harvest. Thanksgiving also bears a resemblance to the ancient Jewish harvest festival of Sukkot.

The first autumn harvest for the newly arrived Pilgrims corresponded with the Wampanoag Indians autumn harvest celebration at Plymouth. This event is widely regarded as America’s First Thanksgiving. Much of the local fare would have been from the Indians harvest.

In November 1621, now remembered as America’s “first Thanksgiving”, although the Pilgrims themselves may not have used the term at the time. The festival lasted for three days.

No exact records exist of the actual menu, but Edward Winslow journaled that after the Pilgrims’ first corn harvest proved successful the colony’s governor, William Bradford sent 4 men hunting for wild turkey, which was plentiful in the region and common food fare for both the Pilgrims and Wampanoag Indians. It is also possible that the hunters also returned with ducks and geese. He was organizing a celebratory feast a celebratory feast and invited a group of the fledgling colony’s Native American allies, including the Wampanoag chief Massasoit.

Historians have suggested that many of the dishes were likely prepared using traditional Native American spices and cooking methods. As for the dressing or stuffing, herbs, onions and nuts may have been added to the birds for flavor.

The first Thanksgiving’s attendees almost certainly got their fill of meat. Winslow wrote that the Wampanoag guests arrived with an offering of five deer. Culinary historians speculate that the deer was roasted on a spit over a smoldering fire and that the colonists might have used some of the venison to whip up a hearty stew.

Local vegetables that likely appeared on the table include onions, beans, lettuce, spinach, cabbage, carrots and perhaps peas. Corn, which records show was plentiful at the first harvest, might also have been served, but not in the way most people enjoy it now. In those days, the corn would have been removed from the cob and turned into cornmeal, which was then boiled and pounded into a thick corn mush or porridge that was occasionally sweetened with molasses.

Fruits indigenous to the region included blueberries, plums, grapes, gooseberries, raspberries and, of course cranberries, which Native Americans ate and used as a natural dye. While the Pilgrims might have been familiar with cranberries by the first Thanksgiving, they wouldn’t have made sauces and relishes with the tart orbs. The Pilgrims would surely have depleted their sugar supplies by this time. Records show that adding sugar to cranberries and using the mixture as a relish didn’t actually happen until about 50 years later.

Because of their location and proximity to the coast, many culinary historians believe that much of the Thanksgiving menu consisted of many seafood entrees that are no longer on today’s menus. Mussels in particular were abundant in New England and could be easily harvested because they clung to rocks along the shoreline. The colonists occasionally served mussels with curds, a dairy product with a similar consistency to cottage cheese. Lobster, bass, clams and oysters might also have been part of the feast.

Whether they were mashed, roasted, white or sweet, potatoes were not at the first Thanksgiving as they had yet to arrive to the north American region. Present on the menu would have been turnips and possibly groundnuts.

As for pumpkin pie, pumpkins and squashes were indigenous to the New England area, but the settlers hadn’t yet constructed an oven and lacked both the butter and flour to have made a pie crust. Some accounts do imply that early settlers improvised by hollowing out pumpkins, filling the shells with milk, honey and spices to make a custard, then roasting the gourds whole in hot ashes. The lack of sugar and an oven would have also eliminate pies, cakes or other desserts from the menu.

Throughout that first brutal winter, most of the colonists remained on board the ship, where they suffered from exposure, scurvy and outbreaks of contagious disease. Only half of the Mayflower’s original passengers and crew lived to see their first New England spring. In March, the remaining settlers moved ashore, where they received an astonishing visit from an Abenaki Indian who greeted them in English. Several days later, he returned with another Native American, Squanto, a member of the Pawtuxet tribe who had been kidnapped by an English sea captain and sold into slavery before escaping to London and returning to his homeland on an exploratory expedition. Squanto taught the Pilgrims, weakened by malnutrition and illness, how to cultivate corn, extract sap from maple trees, catch fish in the rivers and avoid poisonous plants. He also helped the settlers forge an alliance with the Wampanoag, a local tribe, which would endure for more than 50 years and tragically remains one of the sole examples of harmony between European colonists and Native Americans.

Pilgrims didn’t hold their second Thanksgiving celebration until 1623 to mark the end of a long drought that had threatened the year’s harvest and prompted Governor Bradford to call for a religious fast. Days of fasting and thanksgiving on an annual or occasional basis became common practice in other New England settlements as well.

During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress designated one or more days of thanksgiving a year, and in 1789 George Washington issued the first Thanksgiving proclamation by the national government of the United States; in it, he called upon Americans to express their gratitude for the happy conclusion to the country’s war of independence and the successful ratification of the U.S. Constitution. His successors John Adams and James Madison also designated days of thanks during their presidencies.

TRIVIA THOUGHTS

Turkey, because it contains tryptophan often gets blamed for the drowsiness and the need for a nap after the big Thanksgiving meal, but studies suggest it is really the carbohydrate-rich sides and desserts that allow tryptophan to enter the brain.

In September 1620, a small ship called the Mayflower left Plymouth, England, carrying 102 passengers—an assortment of religious separatists seeking a new home where they could freely practice their faith and other individuals lured by the promise of prosperity and land ownership in the New World. After a treacherous and uncomfortable crossing that lasted 66 days, they dropped anchor near the tip of Cape Cod, far north of their intended destination at the mouth of the Hudson River. One month later, the Mayflower crossed Massachusett Bay, where the Pilgrims, as they are now commonly known, began the work of establishing a village at Plymouth.

Beginning in the mid-20th century and perhaps even earlier, the president of the United States has “pardoned” one or two Thanksgiving turkeys each year, sparing the birds from slaughter and sending them to a farm for retirement. A number of U.S. governors also perform the annual turkey pardoning ritual.

New York, In 1817, became the first of several states to officially adopt an annual Thanksgiving holiday; each celebrated it on a different day, however, and the American South remained largely unfamiliar with the tradition. In 1827, the noted magazine editor and prolific writer Sarah Josepha Hale—author, among countless other things, of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”—launched a campaign to establish Thanksgiving as a national holiday. For 36 years, she published numerous editorials and sent scores of letters to governors, senators, presidents and other politicians. Abraham Lincoln, finally heeded her request in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, in a proclamation entreating all Americans to ask God to “commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife” and to “heal the wounds of the nation.”

It was Abraham Lincoln who scheduled Thanksgiving for the final Thursday in November, and it was celebrated on that day every year until 1939, when FDR moved the holiday up a week in an attempt to spur retail sales during the Great Depression. Roosevelt’s plan, known derisively as Franksgiving, was met with passionate opposition, and in 1941 the president reluctantly signed a bill making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday in November.

In many American households, the Thanksgiving celebration has lost much of its original religious significance; instead, it now centers on cooking and sharing a bountiful meal with family and friends.

Volunteering is a common Thanksgiving Day activity, and communities often hold food drives and host free dinners for the less fortunate.

Parades have also become an integral part of the holiday in cities and towns across the United States. Presented by Macy’s department store since 1924, New York City’s Thanksgiving Day parade is the largest and most famous, attracting some 2 to 3 million spectators along its 2.5-mile route and drawing an enormous television audience. It typically features marching bands, performers, elaborate floats conveying various celebrities and giant balloons shaped like cartoon characters.

For some scholars, the jury is still out on whether the feast at Plymouth really constituted the first Thanksgiving in the United States and many Native Americans take issue with how the Thanksgiving story is presented to the American public, and especially to schoolchildren. In their view, the traditional narrative paints a deceptively sunny portrait of relations between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag people, masking the long and bloody history of conflict between Native Americans and European settlers that resulted in the deaths of millions. Since 1970, protesters have gathered on the day designated as Thanksgiving at the top of Cole’s Hill, which overlooks Plymouth Rock, to commemorate a “National Day of Mourning.” Similar events are held in other parts of the country. Historians have recorded other ceremonies of thanks among other European settlers in North America that actually predate the Pilgrims’ celebration.

Save

BACON HERB ROASTED TURKEY

BACON HERB ROASTED TURKEY

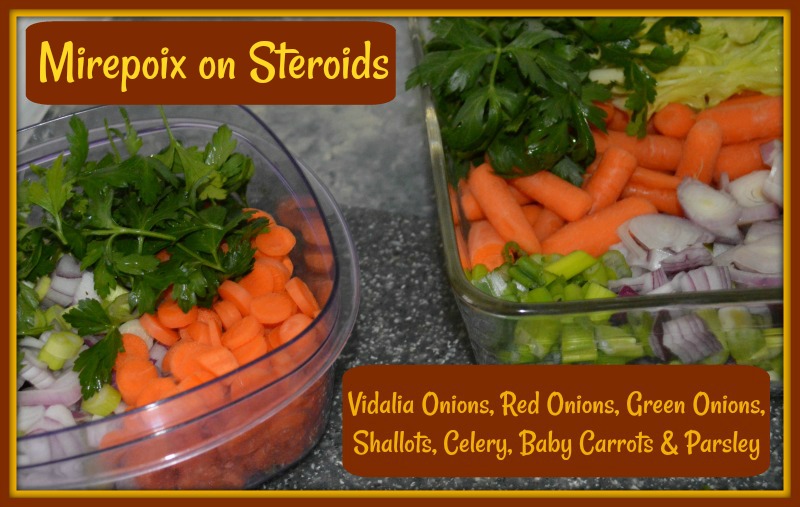

Mirepoix from the French is plainly diced vegetables cooked with butter (generally) on a gentle heat without browning until soft and flavorful. You are not trying to caramelize, but blend and sweeten the flavors to use as a base for other foods.

Mirepoix from the French is plainly diced vegetables cooked with butter (generally) on a gentle heat without browning until soft and flavorful. You are not trying to caramelize, but blend and sweeten the flavors to use as a base for other foods.