Category: HOLIDAYS

DAY 9 ~ BLOGMAS 2017 ~ WINTER WONDERLAND MEMORY PICTURES

I can’t actually get to the disks with pictures from some of our more favorite Christmases so will share these 2013 ones with you. This was a great year as we actually had lots of snow in Oregon. We loved living so close to the Christmas tree farm also. Beautiful trees for reasonable costs unlike here.

The year had been VERY wet which is the normal, but an arctic storm blew in and all of a sudden everything turned white. This was our first snowstorm of the season, just before Christmas.

The year had been VERY wet which is the normal, but an arctic storm blew in and all of a sudden everything turned white. This was our first snowstorm of the season, just before Christmas.The house across the street usually looks REALLY horrible, but NOT when it’s under a blanket of snow.

#AvaTheElf LOVES HER ADVENT CALENDAR BAGS

DAY 8 – BLOGMAS 2017 – FAVORITE CHILDHOOD MEMORY

WOW there are so many! My very first personal is when I was 9, my aunt coming to visit from Texas around that same time and sitting on the floor in a leather dress playing Barrel of Monkeys with the younger kids or maybe the year I got my first bike, whoops wait maybe that was the birthday before Christmas.

WOW there are so many! My very first personal is when I was 9, my aunt coming to visit from Texas around that same time and sitting on the floor in a leather dress playing Barrel of Monkeys with the younger kids or maybe the year I got my first bike, whoops wait maybe that was the birthday before Christmas.

My grandfather worked for General Electric as an X-ray technician of sorts (he oversaw the installation and calibration of X-ray equipment) and one year he brought home a GE Snow tree and ornaments (I still don’t know the correlation between between being an X-ray technician and Christmas trees). Anyway this tree had a HUGE decorated cardboard base and once the tree was up and decorated you filled this base with thousands of tiny Styrofoam balls and when you turned the switch on the tree would make it’s own snow. As a kid I thought it was pretty cool, but as an adult I look back and realize what a MESS it made!! Especially when the wind was blowing and static electricity was high – those damn balls stuck to EVERYTHING!

But wait, that is not my favorite memory. It turns out that my favorite memory is of trying to stump my dad each year with his gift – it became a mission of sorts to be the first to stump him. I swear the man was Carnac when it came to knowing what was inside a box. We tried EVERY year to stump him and I don’t remember ever being able to do it. We tried adding bricks, taping a silver dollar with duct tape to the bottom so it would flip back and forth to make noise when you shook it, adding a pair of shoes… but he ALWAYS guessed! I don’t know how he did it.

But wait, that is not my favorite memory. It turns out that my favorite memory is of trying to stump my dad each year with his gift – it became a mission of sorts to be the first to stump him. I swear the man was Carnac when it came to knowing what was inside a box. We tried EVERY year to stump him and I don’t remember ever being able to do it. We tried adding bricks, taping a silver dollar with duct tape to the bottom so it would flip back and forth to make noise when you shook it, adding a pair of shoes… but he ALWAYS guessed! I don’t know how he did it.REINDEER NIBBLES

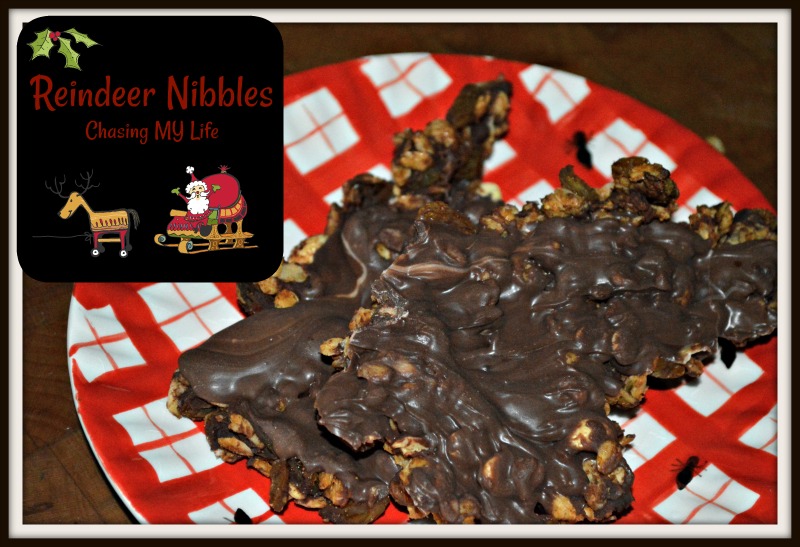

REINDEER NIBBLES

REINDEER NIBBLES

2/3 cup honey

2/3 cup creamy peanut butter

1/2 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon PURE vanilla extract

4 cups regular oats (uncooked)

1 cup unsalted peanuts, slightly chopped

1 1/2 cups golden raisins

1/2 cup semi-sweet chocolate chips

2 cups melted CandyQuick

- Preheat oven to 300°.

- Whisk together the honey, peanut butter and cinnamon in a small sauce pan over medium heat, stirring constantly until thoroughly heated through. DO NOT BOIL.

- Remove from heat and stir in vanilla.

- In a large bowl pour peanut butter mixture over the oatmeal, stir to combine.

- Spread oats in a jelly roll pan sprayed with non-stick cooking spray.

- Bake for 25 minutes, stirring occasionally

- Return oats to large mixing bowl and stir in peanuts, chocolate chips and raisins.

- Spread oat mixture back into jelly roll pan and return to oven.

- Turn oven off and let cool in oven for 90 minutes, stirring occasionally and keeping the door closed.

- Remove from oven.

- Melt CandyQuick in 30 second increments until pourable. Stir after each 30 seconds.

- Pour CandQuick over oat mixture and freeze for 1 hour.

- Break apart into pieces.

- Store in an airtight container.

NOTE: The pieces that are at the bottom make a great granola!

SHARING with FOODIE FRIDAY and TASTY THURSDAY.

#AvaTheElf HELPS WITH THE LIGHTS

DAY 7 ~ BLOGMAS 2017 ~ FAVORITE STORIES

The brand new pastor and his wife, newly assigned to their first ministry, to reopen a church in suburban Brooklyn, arrived in early October excited about their opportunities. When they saw their church, it was very run down and needed much work. They set a goal to have everything done in time to have their first service on Christmas Eve.

They worked hard, repairing pews, plastering walls, painting, etc… and on December 18th they were ahead of schedule and just about finished.

On December 19th a terrible tempest – a driving rainstorm hit the area and lasted for two days.

On the 21st, the pastor went over to the church. His heart sank when he saw that the roof had leaked, causing a large area of plaster about 20 feet by 8 feet to fall off the front wall of the sanctuary just behind the pulpit, beginning about head high.

The pastor cleaned up the mess on the floor, and not knowing what else to do but postpone the Christmas Eve service, headed home. On the way he noticed that a local business was having a flea market type sale for charity so he stopped in. One of the items was a beautiful, handmade, ivory colored, crocheted tablecloth with exquisite work, fine colors and a Cross embroidered right in the center. It was just the right size to cover up the hole in the front wall. He bought it and headed back to the church.

By this time it had started to snow. An older woman running from the opposite direction was trying to catch the bus. She missed it. The pastor invited her to wait in the warm church for the next bus 45 minutes later. She sat in a pew and paid no attention to the pastor while he got a ladder, hangers, etc… to put up the tablecloth as a wall tapestry. The pastor could hardly believe how beautiful it looked and it covered up the entire problem area.

Then he noticed the woman walking down the center aisle. Her face was like a sheet.. ‘Pastor,’ she asked, ‘where did you get that tablecloth?’ The pastor explained. The woman asked him to check the lower right corner to see if the initials, EBG were crocheted into it there. They were. These were the initials of the woman, and she had made this tablecloth 35 years before, in Austria.

The woman could hardly believe it as the pastor told how he had just gotten the Tablecloth. The woman explained that before the war she and her husband were well-to-do people in Austria. When the Nazis came, she was forced to leave. Her husband was going to follow her the next week. He was captured, sent to prison and she never saw her husband or her home again.

The pastor wanted to give her the tablecloth, but she made the pastor keep it for the church. The pastor insisted on driving her home, that was the least he could do. She lived on the other side of Staten Island and was only in Brooklyn for the day for a house cleaning job.

What a wonderful service they had on Christmas Eve The church was almost full. The music and the spirit were great. At the end of the service, the pastor and his wife greeted everyone at the door and many said that they would return. One older man, whom the pastor recognized from the neighborhood continued to sit in one of the pews and stare, and the pastor wondered why he wasn’t leaving.

The man asked him where he got the Tablecloth on the front wall because it was identical to one that his wife had made years ago when they lived in Austria before the war and how could there be two tablecloths so much alike.

He told the pastor how the Nazis came, how he forced his wife to flee for her safety and he was supposed to follow her, but he was arrested and put in a prison. He never saw his wife or his home again all the 35 years in between.

The pastor asked him if he would allow him to take him for a little ride. They drove to Staten Island and to the same house where the pastor had taken the woman three days earlier.

He helped the man climb the three flights of stairs to the woman’s apartment, knocked on the door and he saw the greatest Christmas reunion he could ever imagine.

This true Story was submitted by Pastor Rob Reid.

DAY 6 ~ BLOGMAS 2017 ~ WISH LIST

Participating in BLOGMAS helps get me in and keep me in the Christmas spirit. There is a new prompt for each day. It is a lot of fun to read about each other’s traditions and family recipes and pictures.

Participating in BLOGMAS helps get me in and keep me in the Christmas spirit. There is a new prompt for each day. It is a lot of fun to read about each other’s traditions and family recipes and pictures.

This year we are forgoing BIG gifts again and doing stockings only since this house has eaten up all our disposable cash so fast! We are planning trips after the first of the year to decide 100% where we are going though and calling it our Christmas present to each other.

#AvaTheElf LOVES sleeping with Sady

DAY 5 ~ BLOGMAS 2017 ~ MUST HAVES

What I CANNOT live without in winter is many many things, but these are my top items! The one thing I am absolutely sure of is that if I have a sore throat, dry skin, cold feet or hands, cold food or catch a cold I am NOT happy.

What I CANNOT live without in winter is many many things, but these are my top items! The one thing I am absolutely sure of is that if I have a sore throat, dry skin, cold feet or hands, cold food or catch a cold I am NOT happy.

I drink a cup of green tea every night and try to make very balanced comfort food meals to warm up my family from the inside out. Here are a few of our favorite soups and stews links for you.

Tomato Spinach Soup

Chicken & Sausage Gumbo

#AvaTheElf LOVES to bake!

DAY 4 ~ BLOGMAS 2017 ~ FAVORITE CHRISTMAS MOVIES

Today’s category is an easy one for me. I start taping Christmas movies on Lifetime, Hallmark and INSP as soon as they air so I can watch all year long. I’m a sucker for a happy ending and let’s face it, Christmas movies have happy endings.

So this list could be reallllllllllly long, but I will just keep it to the top 5 MUST watch each and every year movies.